Before the Gari Yala survey in 2020, Professor Nareen Young of the Jumbunna Institute for Indigenous Research and Education says there was a huge gap when it came to recognising Indigenous views on employment.

“Absolute void. Nothing.”

“Policy has been made on the basis of no asking, no information on the views of Indigenous people and what we might think is important in the employment experience and what we might want out of it,” Professor Young says.

The Gari Yala survey – Gari Yala means ‘speak the truth’ in Wiradjuri – is the first of its kind. It’s an on-going survey that will occur every three years.

Young identifies a “glaring omission” in the evolution of ‘Indigenous employment’ into a discipline over the past 25 years.

“Zilch. No discussion about the views of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in how that should operate and what our experiences were in those jobs and those workplaces. And that led to the Gari Yala report,” she says.

Through stories and real-life experiences, Gari Yala enables Indigenous people to speak truth to workplace experiences.

The survey brings together the views of 1,033 Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people through a survey carried out by the Jumbunna Institute for Indigenous Research and Education at UTS and Diversity Council Australia.

The research team note the survey’s results are reflective rather than representative of the views of all Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people.

The ‘cultural load’ and ‘identity strain’

“Staff don’t know how to deal with or talk about Aboriginal issues. So, they say nothing at all,” says one anonymous participant in the Gari Yala survey.

“They’d rather talk about the death of George Floyd in America, but not acknowledge what happens here in Australia.”

Two key terms emerge from the Gari Yala survey that speak to experiences like these: ‘cultural load’ and ‘identity strain’.

So, what do these terms look like in our workplaces?

Cultural load is the additional burden shouldered by Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people in predominately non-Indigenous workplaces.

The ATUI Voice. Treaty. Truth. Advocacy Course will introduce you to:

-

The history of the First Nations peoples’ struggle

-

The Uluru Statement of the Heart

-

Techniques to advocate on behalf of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Workers

-

The skills required to build the confidence to handle objections

-

Messaging and mapping in a targeted campaign

“Because there is such ignorance in the broader Australian community about Indigenous people and our communities and our cultures, it constantly falls on Indigenous people to make up the gaps and fill in the blanks,” Young says.

More than two-thirds of survey participants say they feel expected to talk on behalf of all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in their workplaces.

Similarly, almost two-thirds of respondents describe high levels of identity strain where they feel they must work harder to prove they can do the job or find they are asked to ‘tone it down’ on Indigenous issues.

Young describes ‘identity strain’ as “the pressure that we feel when our identity is not taken seriously or not given full support at work.”

The effort of having to explain your own presence in a workplace over and over again takes a huge toll on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander workers.

A Gari Yala participant describes the effect of identity strain as, “Keeping mental notes and constantly assessing how safe the space is depending on who is in the room.”

Unionised workplaces have a large role to play

“What allies in the employment sector need to do is let it be led by Indigenous people. That’s the ‘Get up! Stand Up!’ focus I think for NAIDOC week,” Young says.

“And listening to mob about what we want out of employment and not making assumptions,” she says.

NAIDOC week is one of the occasions when the cultural load becomes most visible.

Around two-thirds of Gari Yala participants said they were expected to organise NAIDOC week events. Unlike their non-Indigenous colleagues, they are also expected to manage other Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander workers and clients.

Young admits that unions haven’t always been “a 100 per cent great on racism” but nonetheless believes unions are in the best position to be leading the charge in implementing the ‘10 Truths’ outlined in the Gari Yala report.

“Unions understand workplaces,” she says.

Union officials work in workplaces every day and understand the small dynamics and the large dynamics that make workplaces difficult for people – whether it’s because of racism or because of sexism or whatever.

Professor Nareen Young

Jumbunna Institute for Indigenous Research and Education

The 10 Truths are actions employers can take to ensure Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander workers are treated equitably.

These Truths include recognising and addressing identity strain and cultural load as well as actively supporting career development. This means ensuring that the business or organisation is ready to employ Indigenous people rather than simply expecting them to be “work-ready”.

“So, I think unions have a really large role to play in the change that we’re seeking over the next few years,” Young says.

“[That role includes] law reform and really looking wholistically at the way we deal with workplace racism in Australia. And only unions can do that,” she says.

What can union members do at your workplace?

For Young, a culturally safe workplace is, “where the union presence at the workplace is as much about racism as it is about every other industrial entitlement.”

“So, when I say…that anti-racism procedures in workplaces should be industrial entitlement – that goes to the role of unions in enforcing those entitlements.”

This enforcement role means it is up to union members to act straight away when it comes to fostering anti-racist workplaces.

“Delegates should be trained up in the 10 Truths and should be putting them in place in workplaces,” Young says.

So, if you want to see change in your workplace, the most powerful thing you can do is join your union.

As Young explains, workers in unions are at the forefront of enacting cultural safe workplaces.

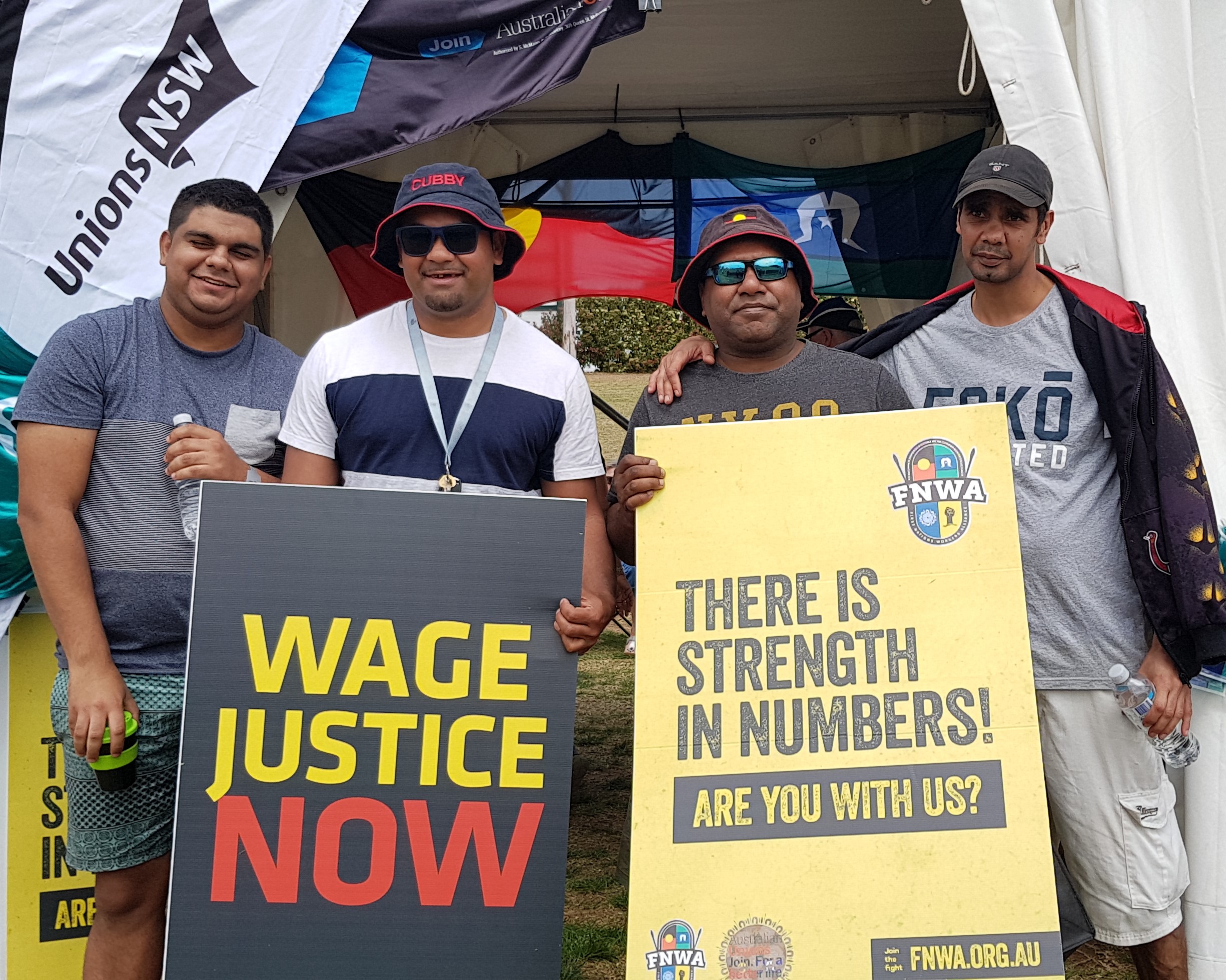

Through the First Nations Workers’ Alliance (FNWA), union members continue to fight for wage justice for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander workers.

FNWA operates like a union for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander workers who do not have access to a union or are not considered workers due to falling under the social security act.

FNWA is culturally safe for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander workers wanting to learn about unions and who want to join their industry union.

All union members can join the Alliance. If you’re not yet a member of a union, now is the best time to join.

SHARE:

Professor Nareen Young on what it means for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander workers to speak truth